Bayes Theorem applied in Python incl. A/B Testing example - Notes

| \ | Frequentist (classical) approach | Bayesian approach |

|---|---|---|

| probability | proportion of outcomes | degree of belief |

| parameters | fixed values/constants | random variables |

| names | confidence interval, p-value, power, significance | credible interval, prior, posterior |

$\Large P(A\mid B)= \frac{P(B\mid A)P(A)}{P(B)}$

$\ P(A\mid B) = Posterior $

$\ P(B\mid A) = Likelihood $

$\ P(A) = Prior $

$\ P(B) = Evidence :(=scaling factor)$

Bayesian estimation

grid approximation

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from scipy.stats import uniform, binom

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

sns.set_style("darkgrid")

# Create cured patients array from 1 to 10

num_patients_cured = np.arange(0,11)

# Create efficacy rate array from 0 to 1 by 0.01

efficacy_rate = np.arange(0,1.01, 0.01)

# Combine the two arrays in one DataFrame

df = pd.DataFrame([(x, y) for x in num_patients_cured for y in efficacy_rate])

# Name the columns

df.columns = ["num_patients_cured", "efficacy_rate"]

# Print df

print(df)

num_patients_cured efficacy_rate

0 0 0.00

1 0 0.01

2 0 0.02

3 0 0.03

4 0 0.04

... ... ...

1106 10 0.96

1107 10 0.97

1108 10 0.98

1109 10 0.99

1110 10 1.00

[1111 rows x 2 columns]

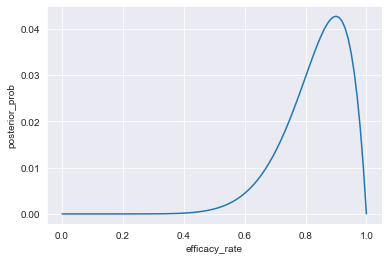

grid approximation without prior knowledge - prior is uniform distribution

# Calculate the prior efficacy rate and the likelihood

df["prior"] = uniform.pdf(df["efficacy_rate"])

df["likelihood"] = binom.pmf(df["num_patients_cured"], 10, df["efficacy_rate"])

# Calculate the posterior efficacy rate and scale it to sum up to one

df["posterior_prob"] = df["prior"] * df["likelihood"]

df["posterior_prob"] /= df["posterior_prob"].sum()

# Compute the posterior probability of observing 9 cured patients

df_9_of_10_cured = df.loc[df["num_patients_cured"] == 9].copy()

df_9_of_10_cured["posterior_prob"] /= df_9_of_10_cured["posterior_prob"].sum()

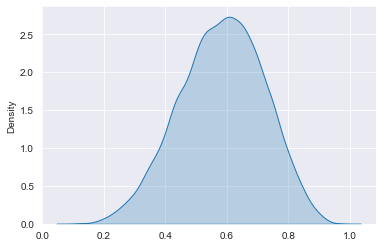

# Plot the drug's posterior efficacy rate having seen 9 out of 10 patients cured.

sns.set_style("darkgrid")

sns.lineplot(x=df_9_of_10_cured["efficacy_rate"], y=df_9_of_10_cured["posterior_prob"] )

plt.show()

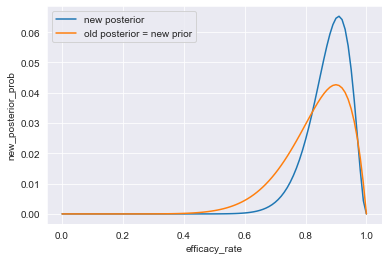

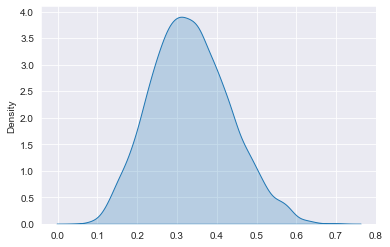

The testing of the drug continues, and a group of additional 12 sick patients have been treated, 10 of whom were cured.

Updating the posterior belief: as prior the previous posterior probability is used

# Assign old posterior to new prior and calculate likelihood

df["new_prior"] = df["posterior_prob"]

df["new_likelihood"] = binom.pmf(df["num_patients_cured"], 12, df["efficacy_rate"])

# Calculate new posterior and scale it

df["new_posterior_prob"] = df["new_prior"] * df["new_likelihood"]

df["new_posterior_prob"] /= df["new_posterior_prob"].sum()

# Compute the posterior probability of observing 10 cured patients

df_10_of_12_cured = df[df["num_patients_cured"] == 10].copy()

df_10_of_12_cured["new_posterior_prob"] /= df_10_of_12_cured["new_posterior_prob"].sum()

sns.lineplot(x=df_10_of_12_cured["efficacy_rate"],

y=df_10_of_12_cured["new_posterior_prob"],

label="new posterior")

sns.lineplot(x=df_9_of_10_cured["efficacy_rate"],

y=df_9_of_10_cured["posterior_prob"],

label="old posterior = new prior")

plt.show()

# compare old and new likelihood

data = {

'likelihood': binom.pmf(df["num_patients_cured"], 10, df["efficacy_rate"])[0:10],

'new likelihood': binom.pmf(df["num_patients_cured"], 12, df["efficacy_rate"])[0:10]

}

pd.DataFrame(data=data)

| likelihood | new likelihood | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 |

| 1 | 0.904382 | 0.886385 |

| 2 | 0.817073 | 0.784717 |

| 3 | 0.737424 | 0.693842 |

| 4 | 0.664833 | 0.612710 |

| 5 | 0.598737 | 0.540360 |

| 6 | 0.538615 | 0.475920 |

| 7 | 0.483982 | 0.418596 |

| 8 | 0.434388 | 0.367666 |

| 9 | 0.389416 | 0.322475 |

binom.pmf(df["num_patients_cured"], 12, df["efficacy_rate"])

array([1. , 0.88638487, 0.78471672, ..., 0.02157072, 0.00596892,

0. ])

Prior distribution

= chosen and stated before we see the data (no cherry picking)

can be

- old prior

- expert opinion

- common knowledge

- previous research

- subjective belief

conjugate priors

= Some priors,multiplied with specic likelihoods, yield known posteriors

for example:

# prior: Beta(a, b)

# posterior: Beta(x, y)

# with

# x = NumberOfSuccesses + a

# y = NumberOfObservations - NumberOfSuccesses + b

Two methods to get the posterior

Simulation

draws = np.random.beta(2,4,1000)

draws[0:10]

array([0.24647378, 0.11933372, 0.38872732, 0.4030806 , 0.59654602,

0.01687355, 0.29056646, 0.14239311, 0.17596316, 0.5461129 ])

#sns.kdeplot(draws)

Calculation

if posterior not know we can calculate using grid approximation

#sns.lineplot(x=df["efficacy_rate"], y=df["posterior_prob"] )

df.head()

| num_patients_cured | efficacy_rate | prior | likelihood | posterior_prob | new_prior | new_likelihood | new_posterior_prob | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 1.0 | 1.000000 | 0.009901 | 0.009901 | 1.000000 | 0.050946 |

| 1 | 0 | 0.01 | 1.0 | 0.904382 | 0.008954 | 0.008954 | 0.886385 | 0.040840 |

| 2 | 0 | 0.02 | 1.0 | 0.817073 | 0.008090 | 0.008090 | 0.784717 | 0.032665 |

| 3 | 0 | 0.03 | 1.0 | 0.737424 | 0.007301 | 0.007301 | 0.693842 | 0.026067 |

| 4 | 0 | 0.04 | 1.0 | 0.664833 | 0.006583 | 0.006583 | 0.612710 | 0.020753 |

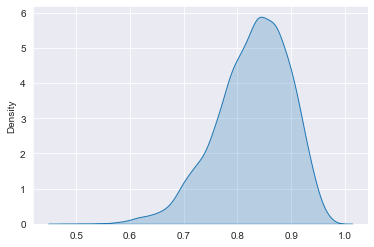

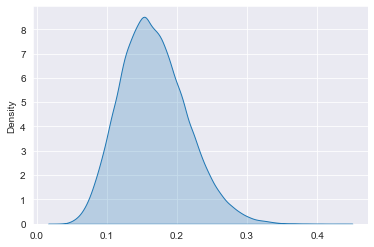

Simulating posterior draws

Beta(5, 2) prior

# Define the number of patients treated and cured

num_patients_treated = 22

num_patients_cured = 19

# Simulate 10000 draws from the posterior distribution

posterior_draws = np.random.beta(num_patients_cured + 5, num_patients_treated - num_patients_cured + 2, 10000)

# Plot the posterior distribution

sns.kdeplot(data=posterior_draws, shade=True)

plt.show()

Reporting Bayesian results

sometimes information on distributions needs to be condensed and single number of a parameter is needed

point estimates

- mean

- median

- credible interval (vs. confidence interval [frequentist])

credible interval

the credible interval is the probability that the parameter falls inside credible interval bounds (vs. confidence interval [frequentist])

# Calculate the expected number of people cured

cured_expected = np.mean(posterior_draws) * 100_000 # 100k infections

# Calculate the minimum number of people cured with 50% probability

min_cured_50_perc = np.median(posterior_draws) * 100_000

# Calculate the minimum number of people cured with 90% probability

min_cured_90_perc = np.percentile(posterior_draws, 10) * 100000

# Print the filled-in memo

print(f"Based on the experiments carried out by ourselves and neighboring countries, \nshould we distribute the drug, we can expect {int(cured_expected)} infected people to be cured. \nThere is a 50% probability the number of cured infections \nwill amount to at least {int(min_cured_50_perc)}, and with 90% probability \nit will not be less than {int(min_cured_90_perc)}.")

Based on the experiments carried out by ourselves and neighboring countries,

should we distribute the drug, we can expect 82798 infected people to be cured.

There is a 50% probability the number of cured infections

will amount to at least 83550, and with 90% probability

it will not be less than 73539.

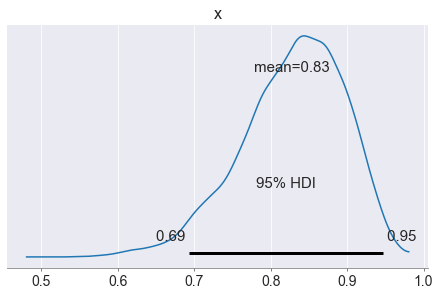

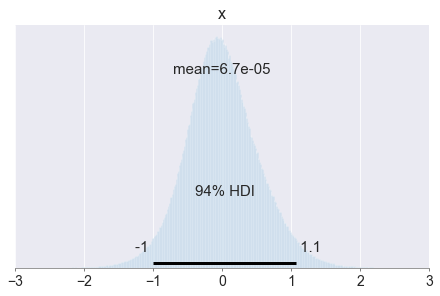

Highest Posterior Density (HPD)

to calculate the credible intervals, as the low and high bounds in which the parameter lies with X% probability

# Import pymc3 as pm

import pymc3 as pm

# hpd function deprecated

# using hdi (highest density interval) instead

ci_67 = pm.hdi(posterior_draws, hdi_prob=0.67)

#print(ci_67)

# Calculate HPD credible interval of 90%

ci_90 = pm.hdi(posterior_draws, hdi_prob=0.9)

# Calculate HPD credible interval of 95%

ci_95 = pm.hdi(posterior_draws, hdi_prob=0.95)

pm.plot_posterior(np.array(posterior_draws), hdi_prob=0.95)

# Print the memo

print(f"The experimental results indicate that with a 90% probability \nthe new drug's efficacy rate is between {np.round(ci_90[0], 2)} and {np.round(ci_90[1], 2)}, \nand with a 95% probability it is between {np.round(ci_95[0], 2)} and {np.round(ci_95[1], 2)}.")

The experimental results indicate that with a 90% probability

the new drug's efficacy rate is between 0.72 and 0.94,

and with a 95% probability it is between 0.69 and 0.95.

Bayesian inference

A/B testing

# 1 heads, 0 tails

tosses = [1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1]

Simulate beta posterior

With Conjugate prior $ Beta(a, b) $ posterior is $ Beta(x, y) $

$ x = \text{NumberOfHeads} + a $

$ y = \text{NumberOfTosses} - \text{NumberOfHeads} + b $

# Set prior parameters and calculate number of successes

beta_prior_a = 1

beta_prior_b = 1

num_successes = np.sum(tosses)

# Generate 10000 posterior draws

posterior_draws = np.random.beta(num_successes + beta_prior_a,

len(tosses) - num_successes + beta_prior_b,

10000)

# Plot density of posterior_draws

sns.kdeplot(posterior_draws, shade=True)

plt.show()

# Set prior parameters and calculate number of successes

beta_prior_a = 1

beta_prior_b = 10

num_successes = np.sum(tosses)

# Generate 10000 posterior draws

posterior_draws = np.random.beta(num_successes + beta_prior_a,

len(tosses) - num_successes + beta_prior_b,

10000)

# Plot density of posterior_draws

sns.kdeplot(posterior_draws, shade=True)

plt.show()

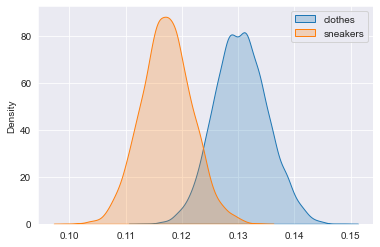

You decide to run A/B testing, modeling the data using the binomial likelihood. You found out that a typical click-through rate for the previous ads has been around 15% recently, with results varying between 5% and 30%. Based on this, you conclude that Beta(10,50) would be a good prior for the click-through rate.

A/B testing - Posterior click rates

two pilot advertising campaigns: one for sneakers, and one for clothes.

ads = pd.read_csv('ads.tsv', delimiter='\t', index_col=0)

ads['time'] = pd.to_datetime(ads['time'])

def simulate_beta_posterior(trials, beta_prior_a, beta_prior_b):

num_successes = np.sum(trials)

posterior_draws = np.random.beta(num_successes + beta_prior_a, len(trials) - num_successes + beta_prior_b, 10000 )

return posterior_draws

ads.head()

| user_id | product | site_version | time | banner_clicked | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| id | |||||

| 0 | f500b9f27ac611426935de6f7a52b71f | clothes | desktop | 2019-01-28 16:47:00 | 0 |

| 1 | cb4347c030a063c63a555a354984562f | sneakers | mobile | 2019-03-31 17:34:00 | 0 |

| 2 | 89cec38a654319548af585f4c1c76b51 | clothes | mobile | 2019-06-02 09:22:00 | 0 |

| 3 | 1d4ea406d45686bdbb49476576a1a985 | sneakers | mobile | 2019-05-23 08:07:00 | 0 |

| 4 | d14b9468a1f9a405fa801a64920367fe | clothes | mobile | 2019-01-28 08:16:00 | 0 |

# Generate prior draws

prior_draws = np.random.beta(10, 50, 100000)

# Plot the prior

sns.kdeplot(prior_draws, shade=True, label="prior")

plt.show()

# Extract the banner_clicked column for each product

clothes_clicked = ads.loc[ads["product"] == "clothes"]["banner_clicked"]

sneakers_clicked = ads.loc[ads["product"] == "sneakers"]["banner_clicked"]

# Simulate posterior draws for each product

clothes_posterior = simulate_beta_posterior(clothes_clicked, 10,50)

sneakers_posterior = simulate_beta_posterior(sneakers_clicked, 10,50)

sns.kdeplot(clothes_posterior, shade=True, label="clothes")

sns.kdeplot(sneakers_posterior, shade=True, label="sneakers")

plt.legend(labels=['clothes', 'sneakers'])

plt.show()

It is more probable that clothes ads are better, but we are not completely sure. We cannot be sure about it, since the two posteriors overlap, so it is actually possible for the sneakers campaign to be bettter.

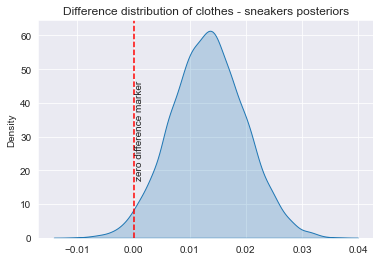

# Calculate posterior difference and plot it

diff = clothes_posterior - sneakers_posterior

sns.kdeplot(diff, shade=True, label="diff")

plt.axvline(x=0, color='red', linestyle='--')

plt.text(0.0002, 32, "zero difference marker", rotation=90, verticalalignment='center')

plt.title('Difference distribution of clothes - sneakers posteriors')

plt.show()

# Calculate and print 90% credible interval of posterior difference

interval = pm.hdi(diff, hdi_prob=0.9)

print(interval)

# Calculate and print probability of clothes ad being better

clothes_better_prob = (diff > 0).mean()

print(clothes_better_prob)

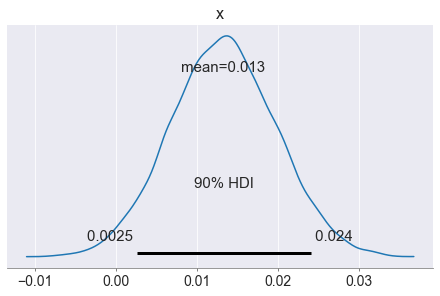

pm.plot_posterior(np.array(diff), hdi_prob=0.9)

plt.show()

[0.00254178 0.02415007]

0.9795

Take a look at the posterior density plot of the difference in click rates: it is very likely positive, indicating that clothes are likely better. The credible interval indicates that with 90% probability, the clothes ads click rate is up to 2.4 percentage points higher than the one for sneakers. Finally, the probability that the clothes click rate is higher is 98%. Great! But there is a 2% chance that actually sneakers ads are better!

Risk analysis

there is a 2% risk that it’s the sneakers ads that are actually better. If that’s the case, how many clicks do we lose if we roll out the clothes campaign?

# Slice diff to take only cases where it is negative

loss = diff[diff < 0]

# Compute and print expected loss

expected_loss = loss.mean()

print(f'maximum loss: {round(expected_loss*100,4)} %')

maximum loss: -0.2422 %

You can safely roll out the clothes campaign to a larger audience. You are 98% sure it has a higher click rare, and even if the 2% risk of this being a wrong decision materializes, you will only lose about 0.2 percentage points in the click rate, which is a very small risk!

Decision analysis

translate parameters to relevant metrics to inform decision making

From posteriors to decisions

- In order to take strategic decisions, one should know the probabilities of different scenarios.

- Bayesian methods allow us to translate parameters into relevant metrics easily.

- Change the unit to which decision takes place in, e.g. CTR dist * impressions * revenue/click = revenue dist

# Calculate distributions of the numbers of clicks for clothes and sneakers

clothes_num_clicks = clothes_posterior * 10_000

sneakers_num_clicks = sneakers_posterior * 10_000

# Calculate cost distributions for each product and platform

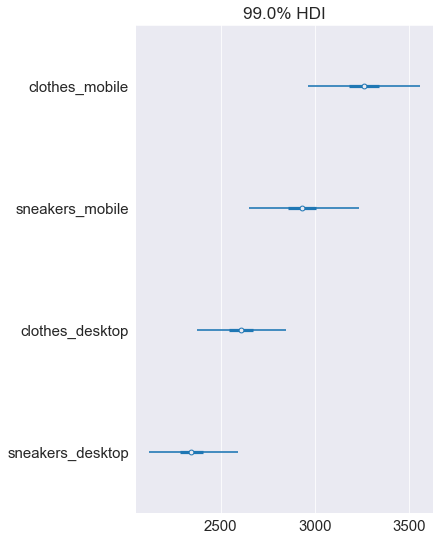

ads_costs = {

"clothes_mobile": clothes_num_clicks * 2.5,

"sneakers_mobile": sneakers_num_clicks * 2.5,

"clothes_desktop": clothes_num_clicks * 2,

"sneakers_desktop": sneakers_num_clicks * 2,

}

# Draw a forest plot of ads_costs

pm.plot_forest(ads_costs, hdi_prob=0.99, textsize=15)

plt.show()

The ends of the whiskers mark the 99% credible interval, so there is a 1% chance the cost will fall outside of it. It’s very, very unlikely, but there is a slim chance that the clothes-mobile cost will turn out lower. It’s important to stay cautious when communicating possible scenarios – that’s the thing with probability, it’s rarely the case that something is ‘completely impossible’!

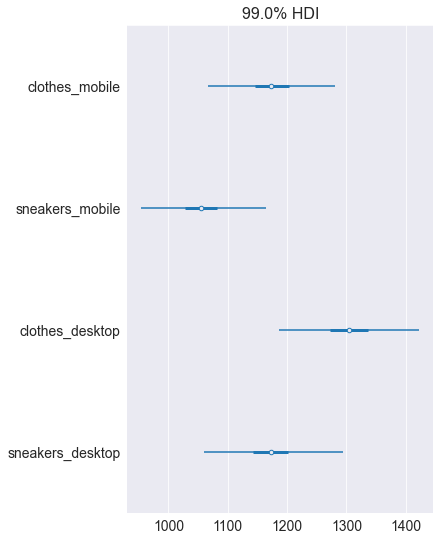

# Calculate profit distributions for each product and platform

ads_profit = {

"clothes_mobile": clothes_num_clicks * 3.4 - ads_costs["clothes_mobile"],

"sneakers_mobile": sneakers_num_clicks * 3.4 - ads_costs["sneakers_mobile"],

"clothes_desktop": clothes_num_clicks * 3 - ads_costs["clothes_desktop"],

"sneakers_desktop": sneakers_num_clicks * 3 - ads_costs["sneakers_desktop"],

}

# Draw a forest plot of ads_profit

pm.plot_forest(ads_profit, hdi_prob=0.99)

plt.show()

Notice how shifting focus from costs to profit has changed the optimal decision. The sneakers-desktop campaign which minimizes the cost is not the best choice when you care about the profit. Based on these results, you would be more likely to invest in the clothes-desktop campaign, wouldn’t you? Let’s continue to the final lesson of this chapter, where we look at regression and forecasting, the Bayesian way!

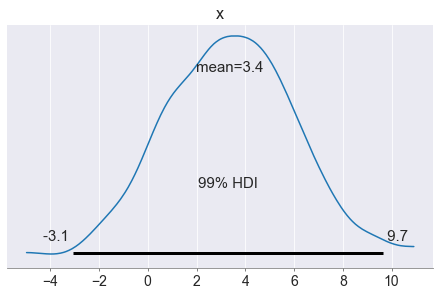

Regression and forecasting

Your linear regression model has four parameters: the intercept, the impact of clothes ads, the impact of sneakers ads, and the variance.

Analyzing regression parameters

#list the files

filelist = ['intercept_draws.txt', 'clothes_draws.txt', 'sneakers_draws.txt', 'sd_draws.txt']

#read them into pandas

df_list = [pd.read_csv(file, names=['col']) for file in filelist]

#concatenate them together

posterior_draws_df = pd.concat(df_list, axis=1)

posterior_draws_df.columns=['intercept_draws', 'clothes_draws', 'sneakers_draws', 'sd_draws']

# Describe parameter posteriors

draws_stats = posterior_draws_df.describe()

print(draws_stats)

# Plot clothes parameter posterior

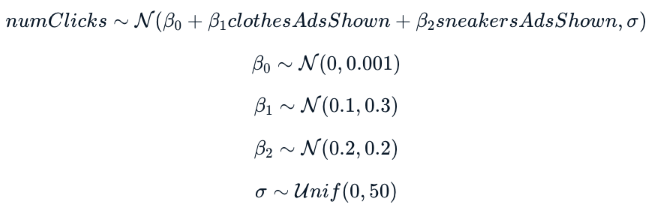

pm.plot_posterior(np.array(posterior_draws_df.clothes_draws), hdi_prob=0.99)

plt.show()

intercept_draws clothes_draws sneakers_draws sd_draws

count 2000.000000 2000.000000 2000.000000 2000.000000

mean 1.280420 0.104594 0.103594 2.651661

std 0.903845 0.030282 0.031596 0.159491

min -2.088446 -0.007500 0.001084 2.211899

25% 0.712354 0.085381 0.081577 2.543340

50% 1.288362 0.104680 0.103554 2.639033

75% 1.849244 0.123830 0.125466 2.754714

max 4.343638 0.229886 0.211751 3.278124

The impact parameters of both clothes and sneakers look okay: they are positive, most likely around 0.1, indicating 1 additional click from 10 ad impressions, which makes sense. Let’s now use the model to make predictions!

Let’s now use the linear regression model to make predictions. How many clicks can we expect if we decide to show 10 clothes ads and 10 sneaker ads?

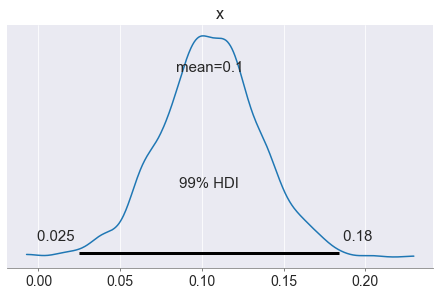

Predictive distribution

Let’s now use the linear regression model to make predictions. How many clicks can we expect if we decide to show 10 clothes ads and 10 sneaker ads?

# Aggregate posteriors of the parameters to point estimates

intercept_coef = np.mean(posterior_draws_df.intercept_draws)

sneakers_coef = np.mean(posterior_draws_df.sneakers_draws)

clothes_coef = np.mean(posterior_draws_df.clothes_draws)

sd_coef = np.mean(posterior_draws_df.sd_draws)

# Calculate the mean of the predictive distribution

pred_mean = intercept_coef + sneakers_coef * 10 + clothes_coef * 10

# Sample 1000 draws from the predictive distribution

pred_draws = np.random.normal(pred_mean, sd_coef, size=1000)

# Plot the density of the predictive distribution

pm.plot_posterior(pred_draws, hdi_prob=0.99)

plt.show()

It looks like you can expect more or less three or four clicks if you show 10 clothes and 10 sneaker ads.

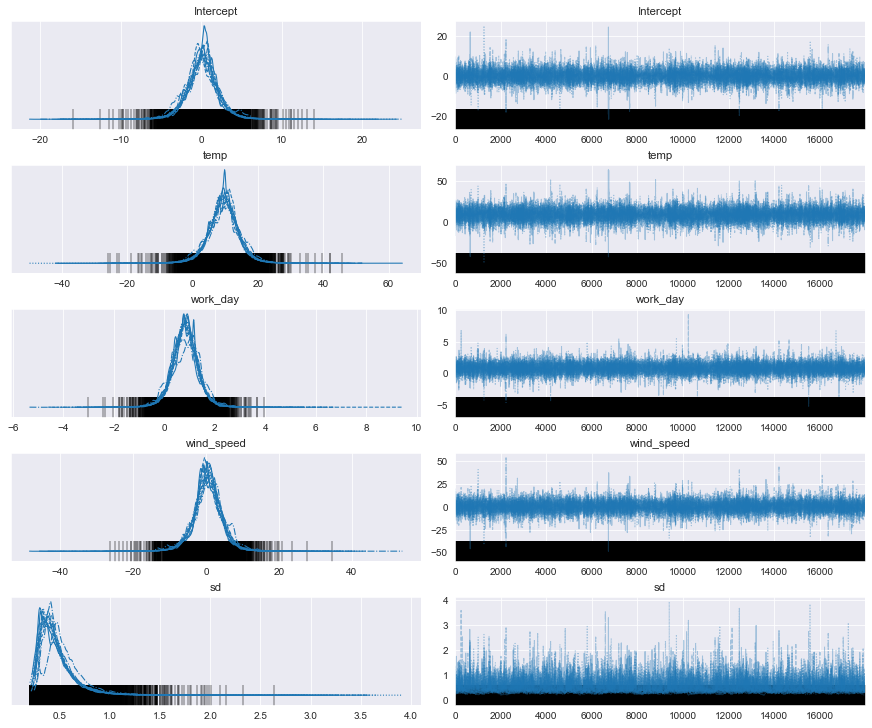

Bayesian linear regression with pyMC3

Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) and model fitting

Problems of Bayesian data analysis in production:

- Grid approximation: inconvenient with many parameters

- Sampling from known posterior: requires conjugate priors

Solution:

- Markov Chains Monte Carlo: sampling from unknown posterior -> same result like others but most flexible

Monte Carlo

Approximating some quantity by generating random numbers

Markov Chains

Markov Chains model a sequence of states, between which one transitions with given probabilities

New Use Case

predict the number of bikes rented per day to plan staff and repairs accordingly

import pandas as pd

import pymc3 as pm

import seaborn as sns

# datacamp has made an error and only provided the test data, no training file downloadable

bikes_test = pd.read_csv('bikes_test.csv')

# very small dataset of just 10 observations

bikes_test.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 10 entries, 0 to 9

Data columns (total 5 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 work_day 10 non-null int64

1 temp 10 non-null float64

2 humidity 10 non-null float64

3 wind_speed 10 non-null float64

4 num_bikes 10 non-null float64

dtypes: float64(4), int64(1)

memory usage: 528.0 bytes

# simple model

formula_first_model = "num_bikes ~ temp + work_day"

# Generate predictive draws

with pm.Model() as model:

pm.GLM.from_formula(formula_first_model, data=bikes_test,

)

print(model)

posterior_predictive_first_model = pm.sample(draws=18000, tune=18000, chains=12, cores=6, return_inferencedata=True)

The glm module is deprecated and will be removed in version 4.0

We recommend to instead use Bambi https://bambinos.github.io/bambi/

Auto-assigning NUTS sampler...

Initializing NUTS using jitter+adapt_diag...

Intercept ~ Flat

temp ~ Normal

work_day ~ Normal

sd_log__ ~ TransformedDistribution

sd ~ HalfCauchy

y ~ Normal

Multiprocess sampling (12 chains in 6 jobs)

NUTS: [sd, work_day, temp, Intercept]

Sampling 12 chains for 18_000 tune and 18_000 draw iterations (216_000 + 216_000 draws total) took 215 seconds.

There were 1559 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

The acceptance probability does not match the target. It is 0.6937498861112372, but should be close to 0.8. Try to increase the number of tuning steps.

There were 1081 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

There were 475 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

There were 3079 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

The acceptance probability does not match the target. It is 0.5765400788999024, but should be close to 0.8. Try to increase the number of tuning steps.

There were 1956 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

The acceptance probability does not match the target. It is 0.6623325935424444, but should be close to 0.8. Try to increase the number of tuning steps.

There were 920 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

There were 691 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

There were 703 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

There were 252 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

There were 779 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

There were 1530 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

The acceptance probability does not match the target. It is 0.7154111570610734, but should be close to 0.8. Try to increase the number of tuning steps.

There were 550 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

The number of effective samples is smaller than 10% for some parameters.

pm.summary(posterior_predictive_first_model)

| mean | sd | hdi_3% | hdi_97% | mcse_mean | mcse_sd | ess_bulk | ess_tail | r_hat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.352 | 0.647 | -0.892 | 1.551 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 29035.0 | 52519.0 | 1.0 |

| temp | 9.050 | 2.919 | 3.644 | 14.619 | 0.017 | 0.012 | 26739.0 | 46236.0 | 1.0 |

| work_day | 0.796 | 0.371 | 0.097 | 1.498 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 34369.0 | 54533.0 | 1.0 |

| sd | 0.396 | 0.147 | 0.190 | 0.651 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 3454.0 | 1887.0 | 1.0 |

# Extend the model with the parameter wind speed

# Define the formula

formula = "num_bikes ~ temp + work_day + wind_speed"

# Generate predictive draws

with pm.Model() as model:

pm.GLM.from_formula(formula, data=bikes_test,

)

print(model)

posterior_predictive = pm.sample(draws=18000, tune=18000, chains=12, cores=6, return_inferencedata=True)

The glm module is deprecated and will be removed in version 4.0

We recommend to instead use Bambi https://bambinos.github.io/bambi/

work_day temp humidity wind_speed num_bikes

0 0 0.265833 0.687917 0.175996 2.947

1 1 0.282609 0.622174 0.153800 3.784

2 1 0.354167 0.496250 0.147379 4.375

3 1 0.256667 0.722917 0.133721 2.802

4 1 0.265000 0.562083 0.194037 3.830

Intercept ~ Flat

temp ~ Normal

work_day ~ Normal

wind_speed ~ Normal

sd_log__ ~ TransformedDistribution

sd ~ HalfCauchy

y ~ Normal

Auto-assigning NUTS sampler...

Initializing NUTS using jitter+adapt_diag...

Multiprocess sampling (12 chains in 6 jobs)

NUTS: [sd, wind_speed, work_day, temp, Intercept]

Sampling 12 chains for 18_000 tune and 18_000 draw iterations (216_000 + 216_000 draws total) took 322 seconds.

There were 6090 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

The acceptance probability does not match the target. It is 0.4535070540886654, but should be close to 0.8. Try to increase the number of tuning steps.

There were 484 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

There were 3314 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

The acceptance probability does not match the target. It is 0.6322839508323852, but should be close to 0.8. Try to increase the number of tuning steps.

There were 5749 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

The acceptance probability does not match the target. It is 0.4657185678254947, but should be close to 0.8. Try to increase the number of tuning steps.

There were 1988 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

There were 1572 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

There were 3831 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

The acceptance probability does not match the target. It is 0.603721265287982, but should be close to 0.8. Try to increase the number of tuning steps.

There were 5848 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

The acceptance probability does not match the target. It is 0.4531228873120186, but should be close to 0.8. Try to increase the number of tuning steps.

There were 5826 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

The acceptance probability does not match the target. It is 0.47532685097020505, but should be close to 0.8. Try to increase the number of tuning steps.

There were 2830 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

The acceptance probability does not match the target. It is 0.6774930920115295, but should be close to 0.8. Try to increase the number of tuning steps.

There were 4966 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

The acceptance probability does not match the target. It is 0.528125701676579, but should be close to 0.8. Try to increase the number of tuning steps.

There were 2743 divergences after tuning. Increase `target_accept` or reparameterize.

The acceptance probability does not match the target. It is 0.6825571279708497, but should be close to 0.8. Try to increase the number of tuning steps.

The number of effective samples is smaller than 10% for some parameters.

# 313sec

#pm.save_trace(trace=posterior_predictive, directory='C://Users//SD//Bayes_Theorem_applied_in_Python//trace.dump', overwrite=True)

pm.summary(posterior_predictive)

| mean | sd | hdi_3% | hdi_97% | mcse_mean | mcse_sd | ess_bulk | ess_tail | r_hat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.148 | 2.044 | -3.759 | 3.984 | 0.034 | 0.024 | 3097.0 | 5728.0 | 1.01 |

| temp | 9.445 | 4.916 | 0.149 | 18.606 | 0.072 | 0.051 | 3878.0 | 6208.0 | 1.00 |

| work_day | 0.824 | 0.542 | -0.198 | 1.828 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 3356.0 | 10050.0 | 1.01 |

| wind_speed | 0.427 | 4.060 | -7.275 | 8.045 | 0.065 | 0.046 | 3170.0 | 6536.0 | 1.00 |

| sd | 0.471 | 0.190 | 0.224 | 0.793 | 0.006 | 0.004 | 507.0 | 850.0 | 1.03 |

# reference

# https://bookdown.org/rdpeng/advstatcomp/monitoring-convergence.html#gelman-rubin-statistic

# r_hat 1.1 or 1.2 as close to mean that all chains have reasonably converged

pm.plot_trace(posterior_predictive)

plt.show()

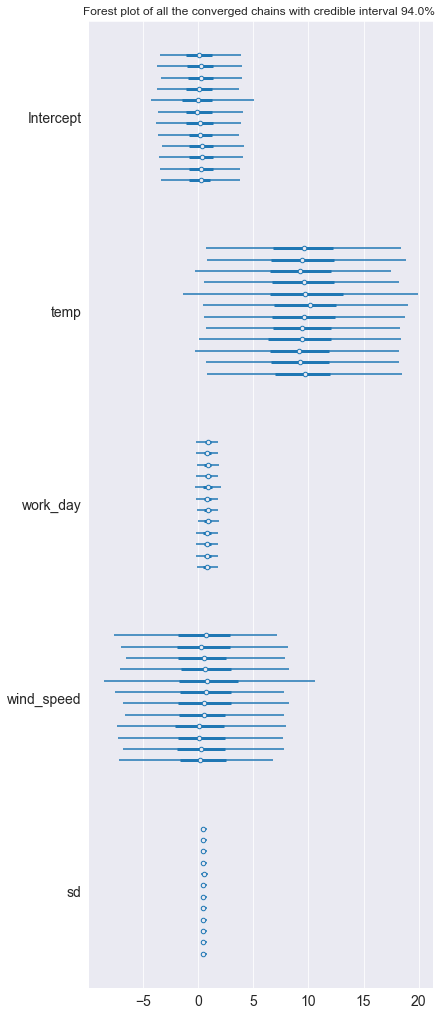

hdi_prob = 0.94

pm.plot_forest(posterior_predictive, hdi_prob=hdi_prob)

plt.title(f'Forest plot of all the converged chains with credible interval {hdi_prob*100}% ')

plt.show()

Interpret results and compare the two models

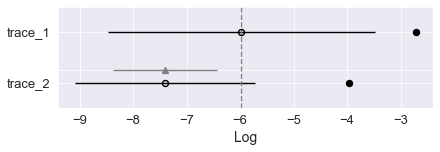

We use the Widely Applicable Information Criterion to compare the two models. Here trace 1 as our first simpler model proves to be better a fit for the data with its higher waic score in pmyc’s comparison function. In the weight column each model’s probability of being the true model is shown, here the extended model with wind speed is clearly worse than the simple one.

import warnings

warnings.simplefilter('ignore')

comparison = pm.compare({"trace_1": posterior_predictive_first_model,

"trace_2": posterior_predictive},

ic='waic')

comparison

| rank | waic | p_waic | d_waic | weight | se | dse | warning | waic_scale | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| trace_1 | 0 | -5.979267 | 3.269994 | 0.000000 | 1.0 | 2.500034 | 0.000000 | True | log |

| trace_2 | 1 | -7.404534 | 3.447594 | 1.425267 | 0.0 | 1.684752 | 0.974662 | True | log |

pm.compareplot(comparison, textsize=13)

# empty circles are the waic scores

# black bars as standard deviations

<AxesSubplot:xlabel='Log'>

Making predictions

# predict with fresh test data

with pm.Model() as model:

pm.GLM.from_formula(formula_first_model, data=bikes_test)

predictive_dist = pm.fast_sample_posterior_predictive(posterior_predictive_first_model)

The glm module is deprecated and will be removed in version 4.0

We recommend to instead use Bambi https://bambinos.github.io/bambi/

predictive_dist['y'].shape

(216000, 10)

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Initialize errors

errors = []

# Iterate over rows of bikes_test to compute error per row

for index, test_example in bikes_test.iterrows():

error = predictive_dist["y"][:, index] - test_example["num_bikes"]

errors.append(error)

# Reshape errors

error_distribution = np.array(errors).reshape(-1)

# Plot the error distribution

pm.plot_posterior(error_distribution, kind='hist')

plt.xlim([-3, 3])

plt.show()

In practice, you might want to compute the error estimate based on more than just 10 observations, but you can already see some patterns. For example, the error is very marginal the error is more often negative than positive, which means that the model tends to underpredict the number of bikes rented!